"I believe that the study of Christian culture is the missing link which is essential to supply if the tradition of Western education and Western culture is to survive, for it is only through this study that we can understand how Western culture came to exist and what are the essential values for which it stands." - Christopher Dawson (1953)

The Humanistic Studies Program was the idea of the distinguished British historian Christopher Dawson. In a series of publications, beginning with a 1953 article in Commonweal magazine, Dawson recommended that the achievements of Christian culture in history, literature, art, and social and spiritual thought be studied as an integrated whole. He aimed to restore a semblance of unity to the university curriculum, which in his view was excessively specialized, "a sprawling collection of unrelated units." He also sought to initiate students into a great living tradition, providing them with a perspective on contemporary issues.

Dawson's innovative ideas attracted the attention of Bruno P. Schlesinger, a history professor at Saint Mary's, who persuaded its president, Sister Madeleva, to adopt Dawson's plan as the basis for a new major. Dawson heartily endorsed the Saint Mary's experiment, and became a consultant in the early stages of its development. With Professor Schlesinger as chair and sole faculty member, thirteen pioneering students helped launch the Program for Christian Culture in the fall of 1956. An impressive array of scholars and writers, including Thomas Merton, lent their enthusiastic support to its establishment.

Because of frequent misunderstandings on the part of students and parents, the title of the Program was changed in 1967 to Humanistic Studies. Over the decades, the department has grown, but it remains committed to its founding ideals. About a dozen students a year now sign up for the major, taught by three full-time faculty members.

In 2006 the department celebrated its 50th anniversary. Alumnae from around the country joined current Humanistic Studies majors for two days of colloquia, reflection, and social events, and the revival of the Christian Culture Lecture series. Ever since its inception, the Program has enjoyed a reputation as one of the most intellectually stimulating and academically challenging departments at Saint Mary's; its graduates are among the most accomplished alumnae of the College.

New Book Honors Life of Bruno Schlesinger

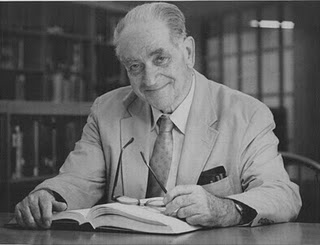

A new book pays tribute to one of Saint Mary’s most beloved professors, Dr. Bruno P. Schlesinger, who died in 2010 at the age of 99. Bruno Schlesinger: A Life in Learning & Letters, edited by Rick Regan, was published in August and available at Amazon.com.

Schlesinger founded the Program for Christian Culture in 1956 and served as the long-time chair of the department, later renamed Humanistic Studies. In 1957, he inaugurated a lecture series that eventually brought over one hundred distinguished scholars to campus, and in 2006 the series was revived in his honor as the Christian Culture Lecture. During his 60-year teaching career, he received many honors, including an honorary doctorate from Saint Mary’s in 1994.

“This little book is a delightful, moving remembrance of Bruno,” says Professor Philip Hicks, department chair of Humanistic Studies. “It belongs on the bookshelf of every Christian Culture/Humanistic Studies graduate—anyone interested in Saint Mary’s, for that matter.”

The nucleus of the book is a chapter by Notre Dame historian Philip Gleason, “From Vienna to South Bend: A Refugee Professor’s Story.” Based on new interviews and research in the Saint Mary’s archives, Gleason’s essay provides the fullest account yet of Schlesinger’s public and private life, including his harrowing flight from Nazism, interrogation by the Gestapo, and month spent in a French jail.

Other contributors to the volume include Schlesinger’s son, Tom, his former colleague, Professor Gail Porter Mandell (Bruno P. Schlesinger Chair in Humanistic Studies Emerita), his friend Father Marvin R. O’Connell (another Notre Dame historian), and alumnae Patricia Ferris McGinn and Mary Griffin Burns. Also featured is a letter to Schlesinger written by the noted spiritual writer, Thomas Merton.

The book is illustrated with several black and white photographs, including childhood and wedding photos. Schlesinger was married for 70 years to Alice Teweles, a book illustrator and portrait artist who died in 2012. Several of Mrs. Schlesinger’s paintings are displayed on the Saint Mary’s campus. Her portrait of former Saint Mary’s president Sister Madeleva is now showcased on the ground floor of Madeleva Hall. It was Sister Madeleva who gave final approval for the Program for Christian Culture, after months of lobbying by Bruno Schlesinger for this experimental curriculum.

Professor Bruno P. Schlesinger (1911-2010)

In 2010, the department mourned the loss of its founder, Bruno P. Schlesinger, who died on September 2nd. At a memorial prayer service in Regina Chapel, his family and former students, together with faculty, administrators, and staff, celebrated his life. Eulogies were offered by his youngest son, Tom Schlesinger, and by Gail Mandell, Bruno P. Schlesinger Chair in Humanistic Studies Emerita.

At the 2011 Reunion, another memorial service was held, which featured remarks by a number of alumnae, including Paula Lawton Bevington '58.

Paula Lawton Bevington:

BRUNO SCHLESINGER

A REMINISCENCE

"Not long after my Saint Mary’s days, at a moment lost somewhere in the tumble of time, I waited for a store clerk to total my purchase. “With the tax,” she droned, “that comes to $14.14.” My reply was automatic: “The Council of Constance!” The clerk, baffled, did not comment. I realized, neither for the first nor the last time, how deeply in my psyche the lessons of Christian Culture were ingrained, and what a powerful influence Bruno Schlesinger had been in my life.

"If I had to use just one word to describe Bruno—a nearly impossible task—it would be “integrity”, defined as a moral, a personal and an intellectual characteristic. It verges on the redundant to state that Bruno’s moral integrity shone. He lived a life of truth. His personal life was built on integrity, manifest in his devotion to his family, to the faith for which he searched and then embraced, to his students. Intellectually, Bruno’s integrity was literal, straight from the root of the word: wholeness. He approached knowledge not as lists of facts, not catalogs of events, but as ideas that inevitably led to other ideas, to conclusions and corrections, to argument and agreement. He found a kindred spirit in Christopher Dawson, fashioned Dawson’s writings into a demanding curriculum and introduced successive generations of adventurous students to the heady excitement of wholeness. Nothing lives in isolation, ideas are alive in human minds, everything and everyone is connected. Participating in Bruno’s classroom discussions—each one was a colloquium—changed us permanently into appreciators of integrity, always seeking the connections that explain the why of the human pilgrimage and our own journeys. For opening our eyes to intellectual integrity, we are grateful to Bruno. I give thanks for his life."

Gail Mandell:

“’He was a man of angel's wit and singular learning; I know not his fellow. For where is the man of that gentleness, lowliness, and affability? And as time requireth, a man of marvellous mirth and pastimes; and sometimes of as sad gravity: a man for all seasons.’ Those words were famously written of Thomas More, the 16th century saint and humanist, whom Bruno Schlesinger chose as the patron saint of the Christian Culture/ Humanistic Studies Program. They describe Bruno himself equally well. Like his hero More, Bruno was indeed a man of sparkling wit, deep wisdom, and extraordinary learning. He, too, delighted in good company--usually over lunch or tea in Bruno’s case. Also like More, Bruno was a man of great emotional complexity. He could be genial, stern, sweet, stubborn, shy, sly, tough, vulnerable. He was a man whose religious faith supported his life’s journey and inspired his life’s work. Born a Jew, Bruno’s faith sprang from the faith of Moses, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and his faith both before and after his conversion to Christianity was, as the passage from the Gospel of Luke so joyfully puts it, a faith in ‘a God of the living’--a God whose spirit, as Paul writes, renews us daily.

“I was privileged to know Bruno for almost 40 years and to work side by side with him for over 30 of them. That’s quite a few seasons, and every season I spent with Bruno brought revelations and surprises. He was already over sixty when we met, which for most of us begins the winter of life, but Bruno was born in the spring, and his spirit was eternally spring-like. There was a child-like playfulness about him, and it came out most obviously around children, in whom he took special delight. Some of us will remember the big bulletin board outside his office, which was papered not with wise quotations or reproductions of famous works of art but with snapshots of alums and their children and, eventually, their grandchildren. When alums brought their kids back to visit, as they often did, Bruno dropped everything and brought out his toys and stash of goodies: his ‘perpetual motion’ bird (not even Einstein could figure out how that thing worked, he always pointed out), his giant-sized M& M dispenser, and his Pepperidge Farm cookies (he loved those Milanos).

“I could easily imagine Bruno as a boy sneaking a ride on one of the bikes in his parents’ bicycle, motorcycle, and repair shop in the town near Vienna where he was born. He left his native Austria in 1938, six months after the Nazi occupation. He was in his twenties then, close to finishing a law degree. As old age set in, he took his first and, so far as I’m aware, his only trip back to his motherland. When he returned, he told me that it was as though all the intervening years—his life in America, even his marriage and children—had all been a dream. It was, he said, as though he’d never left Vienna, and it was very hard to leave a second time. What he missed the most, he told me, was life in the city, especially sitting in one of the Viennese coffee shops for hours on end, ordering a strudel with his coffee and talking with his friends about life.

“Not that he didn’t love life here. He had his teaching career, which as he said with characteristic understatement, had worked out ‘pretty well’ for him. He had his ‘Liesl’—the name by which I always heard him address Alice at home-- his four children and, late in life, his four grandchildren. As Alice told me early on, ‘He doesn’t like to talk about himself.’ But every now and then, he’d share a story about John, Mary, Kathy or Tom or about Tom and Kathy’s children, and you realized how enormously proud he was of those too close to his heart for easy words.

“Not true of politics, however, which was his favorite topic, with music and art as close seconds. Those, he eagerly talked about. Art and music engaged his intellect through his emotions, but politics roused his passions—and the more local the politics, the more passionate he could become. He didn’t bother about minor brouhahas, but a serious controversy could occasion multiple daily drop-ins (‘Last time, I promise,’ he’d say after his third or fourth visit. Two minutes later, Bruno in the doorway: ‘Just one more thing—.’) There were nightly phone calls, too, if the issue was a really hot one. At such times, his mind was like a threshing machine, sharp, cutting, sifting, and sorting. Nothing in MY day, however, could match the intense negotiation required to create the Christian Culture Program. It threatened the status quo, and so, he said, his proposal ‘almost died before it could be born.’ In spite of many delays and obstacles, his political acuity combined with his passionate persistence brought the Program of Christian Culture, eventually renamed ‘Humanistic Studies,’ into being.

“And what a triumph it was! Unique in its focus on the study of Christian culture as a way to interpret the modern world, the Program soon became one of the hallmarks of a Saint Mary’s education—the ‘department deluxe,’ as Sister Madeleva called it. Its interdisciplinary curriculum and emphasis on liberal learning have sustained it through more than half a century. The lives and achievements of its alums are the best evidence of the Program’s enduring strength and relevance.

“A large part of the success of the Program was, beyond doubt, Bruno himself and his great gifts as a teacher. His Socratic method, requiring mental discipline and close attention from students, his keen sense of what he called the “unifying threads” of culture as well as the ‘big picture’ of history, his flair for drama, his masterly storytelling, his Puckish sense of humor—all that, plus his great personal charm, ensured that students did not forget him nor what he taught them. Walking through a museum or reading the morning paper, it all comes back, grads tell me. He initiated students into the excitement and wonder of the intellectual life, in a Christian context that engaged their minds and enlarged their faith.

“His students’ praise and affection turned Bruno into the legend he became. As one of his former students put it so well, he became the ‘father of their minds.’ His response? ‘At least, I never mothered them!’ The devotion he inspired in his students resulted not only from their appreciation and gratitude for the education they received but also from the strong personal connection he forged with so many of them. He spent hours conversing with students in his office. His great secret was that he was a superb listener. He was interested in what interested others. It was as though he had a mental file on each of us that reminded him of all we cared about most.

“Watching Bruno, I learned most of what I know about teaching and learning, although his actual advice was scant. Most of what he said came in asides, often in the form of aphorisms, a bit like the cryptic koans a zen master assigns his disciple for meditation. For example, ‘It’s good THEY do the work.’ And: ‘Remind them what they know.’ Or the most severe: ‘They come asking for bread. God forbid we give them stones.’

“Sharing the same birthday, Bruno and I would usually have lunch each April 15th to celebrate. When I turned fifty, he said something to console me that I’ve often repeated to others: ‘Fifty is the prime of life, Professor Mandell. You have the benefit of experience and, if you’re lucky, your body isn’t breaking down yet.’

“As Paul reminds us in his second letter to the Corinthians, even though the outer person inevitably falls into decay, the risen Christ renews the spirit of the inner person day by day. Paul, the tent maker, aptly assures us that as Christians we trust that ‘when the tent that we live in on earth is folded up, there is a house built by God for us, an everlasting home not made by human hands.’ I believe that as we pray together today for Bruno, who has reached his everlasting home, and for his family and all who miss his earthly presence, Bruno is also praying for us, most likely the prayer of Thomas More himself: ‘Pray for me as I shall pray for thee, that we may merrily meet in heaven.’”

On April 18, 2005, the occasion of his retirement after 60 years at Saint Mary's, President Carol Mooney paid the following tribute:

“Dr. Bruno Schlesinger is a true Renaissance man. His abiding interest in music, art, philosophy, and history has made him the embodiment of the humanities on this campus for the past 60 years. His wide ranging curiosity has made him a model of interdisciplinary engagement for students and faculty alike.

“Dr. Schlesinger’s devotion to Saint Mary’s College for the last six decades is matched only by his students’ devotion to him. For many years, he was almost a one-man alumnae association, keeping up contacts with former students through countless letters, telephone calls, and visits. The enormous turnout of alumnae for the 40th anniversary of the Humanistic Studies Program in 1997 was testament to the popularity and influence of this charismatic polymath. One graduate of the program calls him ‘the father of my mind.’ Today he still corresponds with former students, scores of whom sent letters of congratulations last December on the occasion of his retirement.

“If Sister Madeleva dominated the middle third of the twentieth century at Saint Mary’s, it is fitting that we call the second half of the century ‘the Age of Schlesinger.’ His influence on Saint Mary’s College has been that strong. Though most students know him as a much beloved and inspiring teacher, he has also made his mark on this campus by founding one of its most distinctive and successful programs.

“In 1956, as we all know, he founded the Christian Culture Program, later renamed Humanistic Studies. Based on the educational theories of the British historian Christopher Dawson, Dr. Schlesinger’s department studied the ‘Great Books’ and Christianity’s vital role in shaping the Western tradition. His experiment brought national attention to Saint Mary's College, as did his well-known lecture series, which for 24 years brought to campus some of the leading lights of the Catholic intellectual tradition.

“Long before it became fashionable in the rest of the academic world, he pioneered multicultural and cross-disciplinary study at Saint Mary's College. And for decades he did this single handedly – chairing the department, teaching the classes, and running the lecture series. In 1958 he was the first recipient of the Spes Unica Award recognizing outstanding contributions to the College. He has also received the President’s Medal and an honorary degree from Saint Mary’s College."

“A former student wrote the following to Dr. Schlesinger: ‘I gained a depth of understanding – of the world, of faith, intellect, history, politics, art, and even of myself. No matter how confusing the world appears, I am never wholly lost since I can always see the connection to the past, the circle of repeated triumphs, tragedies, successes, and mistakes. This is somehow comforting because hope and faith are always there. Because of you I know that a woman can live a full life of the mind, heart, and soul. I am forever grateful.’ We are all forever grateful, Dr. Schlesinger.

“So, while it is impossible to adequately honor Dr. Schlesinger’s contributions to the intellectual life of Saint Mary's College, it is only fitting that with the utmost gratitude for all he has done for this College for the past 60 years, we bestow upon him the title of Bruno P. Schlesinger Chair in Humanistic Studies Emeritus.”